In this article

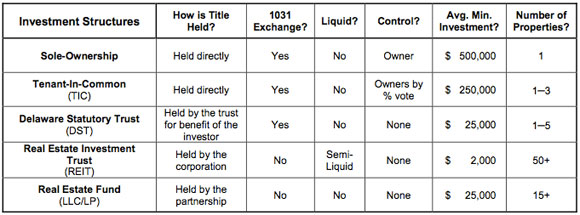

Real estate ownership is often thought of only in the context of owning an entire building or portfolio of buildings outright. Sole-ownership, however, is only one of the multiple investment structures that accommodate real estate ownership and investment participation.  Investors are able to utilize many different types of investment structures for real estate ownership to meet their tax deferment and investment objectives. This article will provide a summary description of each primary investment structure and its particular application to the individual investor. Each of these investment structures can be implemented with the same real estate assets: It is only the investment structure that changes, not necessarily the underlying real estate.

Investors are able to utilize many different types of investment structures for real estate ownership to meet their tax deferment and investment objectives. This article will provide a summary description of each primary investment structure and its particular application to the individual investor. Each of these investment structures can be implemented with the same real estate assets: It is only the investment structure that changes, not necessarily the underlying real estate.

Sole-Ownership

Sole-ownership is the most direct and controlling form of ownership, whereby the owner holds direct title to the entire asset and is able to make all decisions regarding its use, financing, and disposition. If structured properly, sole-ownership investment real estate qualifies for a 1031, 1033, or 721 exchange (UPREIT). The benefit and burden of sole-ownership property is direct control/responsibility. The owner is able to make all of the property-level decisions but is also responsible for the liabilities of the property. Typically, to obtain financing for sole-ownership real estate, owners must sign for recourse debt--which obligates them to pay the debt, regardless of what occurs with the asset. Sole-ownership is best for clients who want to manage and control real estate directly and who have a significant net worth with plenty of liquid funds to purchase and properly maintain larger real estate assets.

One limiting factor of sole-ownership is that is does not facilitate diversification for most higher- net-worth real estate investors. In the case of smaller commercial real estate, such as NN or NNN retail properties with national tenants, sole-ownership typically requires a total purchase price of $1,000,000 to $3,000,000 and a down payment of $500,000 to $1,250,000. With many larger, commercial properties, the sky is the limit on both purchase price and down payment requirements. Most larger, institutional-type commercial assets in stronger locations command purchase prices in excess of $15 million with down payments in excess of $6 million.

For institutional and family office clients with a net worth in excess of $30 million, diversification into smaller commercial real estate via the sole-ownership structure may not be an issue because the available investment funds can be significantly greater. Institutions with investable, available assets in excess of $1 billion are able to build relatively diversified portfolios in both small and large commercial real estate. For most individuals with a net worth of $30 million or less, the sole-ownership investment structure greatly limits the level of diversification possible.

Tenant-in-Common (TIC) Ownership

Tenant-in-Common (TIC) ownership references a way of taking title to real estate with each owner possessing an undivided, fractional interest in an entire property. Tenant-in-Common investment structures began in the 1600s in England. They provided real estate investors an alternative to partnerships. They are popular because of their tax-deferred exchange qualifications. In the past 9 years, the Tenant-in-Common structure has been packaged as an investment security, and it has become common for individual real estate investors in completing their 1031 exchanges.

Tenant-in-Common (TIC) ownership references a way of taking title to real estate with each owner possessing an undivided, fractional interest in an entire property. Tenant-in-Common investment structures began in the 1600s in England. They provided real estate investors an alternative to partnerships. They are popular because of their tax-deferred exchange qualifications. In the past 9 years, the Tenant-in-Common structure has been packaged as an investment security, and it has become common for individual real estate investors in completing their 1031 exchanges.

As the nation's real estate market heated up through the early to mid 2000s, 1031 exchange investing became even more popular. However, the IRS-imposed time restrictions on the 1031 exchange (45 days to identify property; 180 days to close) became difficult for investors to meet. As a result, the Tenant-in-Common structure began to be packaged more regularly as a security in early 2001 and 2002. Investors were able to make much smaller investments to access commercial and institutional quality real estate to complete their 1031 exchange.

Furthermore, many Tenant-in-Common properties came "pre-packaged" with due diligence information and financing already in place. This allowed investors to more easily identify and close on investment real estate and comply with the 1031 guidelines. In 2002, the IRS released Revenue Procedure 2002-22, giving 15 guidelines to consider when using Tenant-in-Common real estate as like-kind replacement property--and with this guidance, the fractionalized real estate industry grew rapidly over the following years.

Whether a Tenant-in-Common structure is applied with two investors or up to 35 investors (the IRS limit), the structure and setup are the same. Owners possess an undivided interest in the property according to their proportionate investment and are able to receive 100% of their share of the potential cash flow, tax benefits, and sale profits from the property. Typically, Tenant-in-Common investments are managed by a third party who is responsible for the day-to-day management decisions at the property level.

Tenant-in-Common real estate functions and can be handled similarly to the practice of sole-ownership, with the exception of the decision making process. Major decisions in Tenant-In- Common properties are governed by a "Tenant-in-Common Agreement." The agreement outlines governance procedures to approve or decline material decisions. Certain decisions-such as refinance or disposition-must be unanimous. The Tenant-in-Common Agreement may include buyout provisions and rules to avoid having any particular investor act as a holdout against the majority of investors.

Tenant-in-Common properties provide investors with access to institutional properties but with smaller minimum investment requirements. Each asset's purchase price can be split among up to 35 separate investors. For example, a $30-million building with 65% financing may require a minimum investment of only $300,000. Lower-cost commercial real estate may accommodate investments of $150,000 or less. The Tenant-in-Common structure allows investors to take title to and participate in large, institutional-type real estate for a fraction of the cost of one-hundred-percent ownership.

The primary drawback to a Tenant-in-Common investment is that any one investor does not have complete control. Each Tenant-in-Common investor is able to vote their percentage interest in ownership for major property decisions. Just like any other type of direct real estate ownership, Tenant-in-Common real estate is generally illiquid. Currently, there is no recognized secondary market to sell an interest, and thus, an individual investor is typically dependent upon the management to execute the businesss plan and sell the property to obtain liquidity. Tenant-in-Common investments are for clients who do not require complete control over all property decisions. This structure is best for clients who are seeking 1031-compatible, institutional-type replacement property managed on their behalf and capable of providing rental income.

Delaware Statutory Trust (DST) Ownership

Similar to the Tenant-in-Common structure, the Delaware Statutory Trust (DST) provides a means of real estate ownership that is undivided, fractional, and compatible with the 1031, 1033, and 721 tax-deferred exchanges. In October of 2004, the IRS provided revenue ruling 2004-86, which defined the Delaware Statutory Trust structure as eligible to be like- kind property. Delaware Statutory Trusts also can be syndicated like Tenant-in-Common investments so that the due diligence information, financing, and closing can be coordinated to accommodate the needs of the 1031 exchange timelines.

In a Tenant-in-Common structure, each owner holds title to the real estate directly. In a Delaware Statutory Trust structure, each investor holds title to the real estate through a beneficial interest in the trust. The DST structure is completely passive. All major property decisions are made by the trustee of the trust and the asset manager, rather than by vote of the Tenant-In- Common owners.

The Delaware Statutory Trust is not limited to 35 investors. It is able to accommodate up to 499 investors. Most firms that provide DST investments do not allow 499 investors in any one asset. But even allowing 50 or 100 investors (up from the 35 person limit of a Tenant-in-Common) can dramatically decrease the minimum investment required for these types of investments. Typically, the minimum investment for DST-structured real estate is $25,000 to $50,000. This accommodates greater diversification opportunities for the individual investor.

The IRS 1031 exchange guidelines for the Delaware Statutory Trust are relatively inflexible. For a DST to qualify for a 1031, it cannot undergo any material change of the leases to the tenants unless there is a tenant bankruptcy or default. Additionally, the DST may not refinance throughout the investment hold period. These requirements limit 1031-qualifying DST investments to assets with large, national tenants with long-term triple-net (NNN) leases and longer-term financing in place. Some providers of DST investments will place a triple-net "master lease" on a multi-tenant property whereby the provider is obligated to pay a certain level of rent to the investors, regardless of what happens to the building's tenants. This allows the underlying leases to be rolled over, renewed, or changed, if need be, without disrupting the 1031 status of the DST.

The primary drawback for the DST is that it is a relatively inflexible ownership structure. It cannot be refinanced or materially adjusted if the need arises. In these circumstances, the DST ownership can be changed into an LLC ownership to provide needed flexibility--but this could impact the future 1031 exchange ability if the structure is not changed back to a DST prior to selling the property. For this reason, the DST structure is not appropriate for assets that have short-term financing or shorter-term leases without a master lease structure in place.

The Delaware Statutory Trust is an investment structure appropriate for clients seeking entirely passive ownership in real estate. This investment structure is best suited for individuals with a net worth greater than $1 million (excluding primary residence) who require 1031-compatible replacement property and are targeting stable income-producing real estate assets with a longer-term hold period and active, third-party professional management.

Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT)

A Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) is a company that exists for the purpose of acquiring, managing, and selling real estate for the benefit of shareholders. REITs are utilized by clients seeking to participate in real estate with the potential for income and capital appreciation, invested primarily in diversified portfolios of commercial real estate. Unlike sole-ownership, Tenant-in-Common, or Delaware Statutory Trust ownership structures, REIT investments cannot be used to accommodate a 1031 or 1033 exchange. Larger REITs typically raise $1-3 billion dollars and build portfolios of investment real estate over a 2-5 years that involve dozens or even hundreds of properties. Though there are items on which REIT shareholders will vote, REITs are primarily passive investments whereby the management makes all of the property- and portfolio-level decisions.

A Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) is a company that exists for the purpose of acquiring, managing, and selling real estate for the benefit of shareholders. REITs are utilized by clients seeking to participate in real estate with the potential for income and capital appreciation, invested primarily in diversified portfolios of commercial real estate. Unlike sole-ownership, Tenant-in-Common, or Delaware Statutory Trust ownership structures, REIT investments cannot be used to accommodate a 1031 or 1033 exchange. Larger REITs typically raise $1-3 billion dollars and build portfolios of investment real estate over a 2-5 years that involve dozens or even hundreds of properties. Though there are items on which REIT shareholders will vote, REITs are primarily passive investments whereby the management makes all of the property- and portfolio-level decisions.

The REIT structure may be used to target any asset class of commercial real estate available. Some REITs are classified by specific asset class, while other REITs will be open to all asset classes to build an internally diversified portfolio. A REIT may target purchases of equity, debt, or a combination of both in its portfolio. These variations allow clients to build selective investment portfolios within the commercial real estate space without requiring large minimum investments that most real estate investing requires. The minimum investment required for non- traded REITs is typically between $1,000 and $5,000, providing clients with a much easier entry point to get exposure to real estate investing.

Another major difference between the REIT and sole-ownership, TIC, and DST investments is that REITs allow the managers to share in a portion of the cash flow and profits. By law, REITs are required to distribute 90% of their taxable income--and upon disposition of the assets in the REIT, the manager typically takes between 5% and 15% of the upside beyond the clients' return of capital invested and a certain level of minimum return per year. Most REITs share in profits after the investors have received a return of their original investment in addition to a minimum range of a 6-10% return on their investment per year.

REITs are best suited for clients who are seeking stable, diversified approaches to real estate investing or who are new to real estate investing in general. REITs are not compatible with or appropriate for 1031 exchange needs. Many REITs are non-traded, meaning that while they have to publicly report their financial information with the SEC, they are not required to trade on a stock exchange. Many REITs have limited early liquidation accommodations for investors who need to get their money out earlier than the REIT hold-period. However, it is important not to count on any sort of early liquidation or invest funds that you may need sooner rather than later. Most non-traded REITs have liquidation targets of about 2-5 years.

The primary drawback to non-traded REITs is that they are illiquid, and though there are secondary markets for non-traded REITs, these markets tend to be very thinly traded. Therefore, investors should only allocate funds to REITs that they can afford to have locked up for an extended period of time.

Real Estate Funds (LLC or LP Structures)

Real estate ownership also can be structured in a Limited Liability Company (LLC) or Limited Partnership (LP) format, pooling multiple investors into a fund that invests in real estate assets. Similar to REITs, real estate funds are passive investments whereby investors rely on centralized, third-party management for the acquisitions, finance, management, and dispositions of real estate. LLC and LP investments cannot be used for an investor's 1031 exchange. Unlike in REITs, LLC and LP investors are members or partners instead of shareholders, and the managing member or general partner in these fund structures is responsible for the management of the real estate in the fund.

Real estate ownership also can be structured in a Limited Liability Company (LLC) or Limited Partnership (LP) format, pooling multiple investors into a fund that invests in real estate assets. Similar to REITs, real estate funds are passive investments whereby investors rely on centralized, third-party management for the acquisitions, finance, management, and dispositions of real estate. LLC and LP investments cannot be used for an investor's 1031 exchange. Unlike in REITs, LLC and LP investors are members or partners instead of shareholders, and the managing member or general partner in these fund structures is responsible for the management of the real estate in the fund.

Real estate funds typically target either higher-risk and higher-return investments or smaller investments that would not justify a more expensive REIT structure. Most real estate funds range in size from $25 million to $50 million in total equity and from $50 million to $150 million in total real estate assets. Many LPs and LLCs are set up to return an investor's original investment and a certain level of return on capital per year before the manager can participate more significantly in the potential profits. Since LLCs and LPs typically are able to admit up to 499 investors in their funds, the investment minimum is typically between $25,000 and $50,000.

Real estate funds are extremely diverse in their range of allowable real estate investments. They can target debt or equity purchases in every type of asset class at any stage of development as outlined in the fund agreement. Real estate fund liquidation dates range between 18 months and 10 years, depending on the fund and the business strategy. That being said, most funds are similar to REITs in that they target 2-5 years for liquidation.

Real estate funds are appropriate for sophisticated clients with a net worth in excess of $1 million (excluding primary residence) who are pursuing higher-risk, higher-return potential strategies in real estate. Real estate funds are not used to complete a 1031 exchange, for investors who want direct management control, or for investors who need near-term liquidity for their original investment. Many real estate funds provide unique management strategies that allow investors to achieve higher risk-adjusted returns that are not correlated with the stock market or other traditional investments.

Common Real Estate Risks

It is important to note that all real estate investments, regardless of their structure, share risks that are common to real estate. Real estate is an illiquid investment. Real estate cannot typically be bought and sold in a day, but rather takes 30-90 days to close in normal transactions. Just because a real estate investment is structured as a DST or Tenant-in-Common investment, this does not remove the illiquidity of the underlying property. That being said, a DST interest does not typically require lender approval, and it may be structurally easier to transfer a DST interest than an entire property. In the case of REITs, if they are publicly traded, they are liquid and can be bought and sold in a day.

All real estate ownership involves closing and management costs of some level or another. Prior to investing, it is important to consider each asset or offering individually to determine whether the costs are reasonable and whether or not the value is appropriate for an investment.